Bellini, Giovanni

(b. c. 1430, Venice [Italy]--d. 1516, Venice), Italian painter

who made Venice a centre of Renaissance art comparable to

Florence and Rome. Although the paintings for the hall of the

Great Council in Venice, considered his greatest works, were

destroyed by fire in 1577, a large number of altarpieces (such

as that in the church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice) and

other extant works show a steady but adventurous evolution

from purely religious, narrative emphasis to a new naturalism

of setting and landscape.

Little is known about Bellini's family. His father, Jacopo, a

painter, was a pupil of Gentile da Fabriano, one of the leading

painters of the 15th-century Gothic revival, and may have

followed him to Florence. In any case, Jacopo introduced the

principles of the Florentine Renaissance to Venice before

either of his sons. Apart from his sons Gentile and Giovanni,

he had at least one daughter, Niccolosa, who married the

painter Andrea Mantegna in 1453. Both sons probably began

as assistants in their father's workshop.

Giovanni's earliest independent paintings were more strongly

influenced by the severe manner of the Paduan school, and

especially of his brother-in-law, Mantegna, than they were by

the graceful style of Jacopo. This influence is evident even

after Mantegna left for the court of Mantua in 1460.

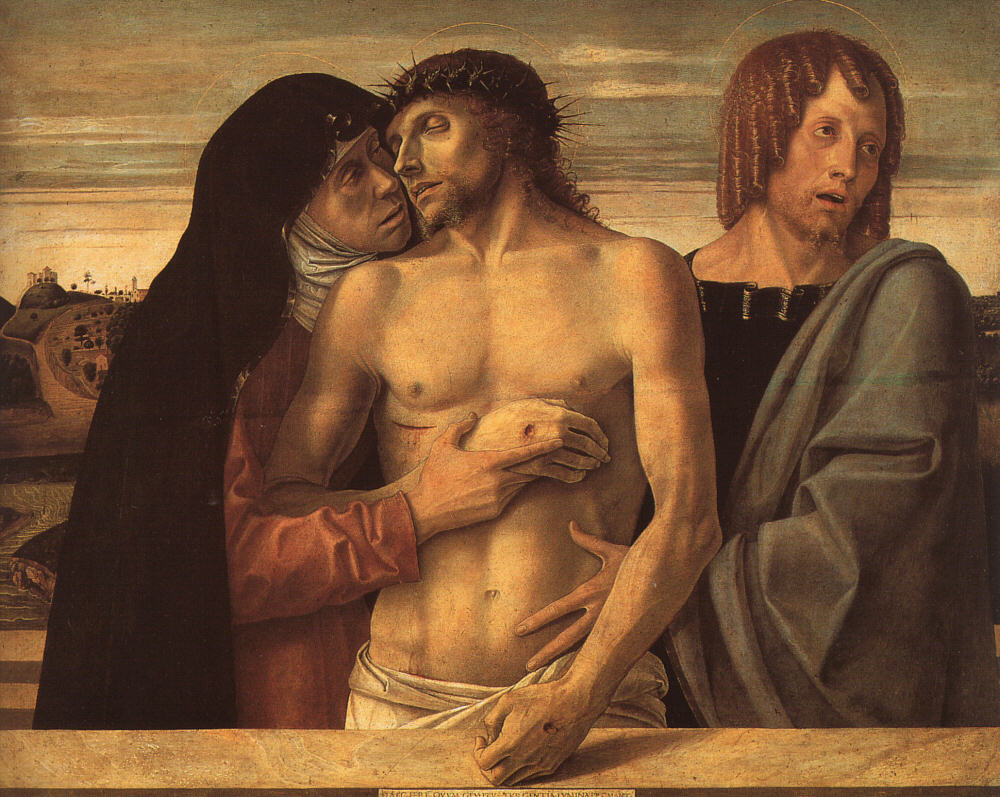

Giovanni's earliest works date from before this period. They

include a "Crucifixion," a "Transfiguration," and a "Dead

Christ Supported by Angels." Several pictures of the same or

earlier date are in the United States and others at the Museo

Civico Correr in Venice. Four triptychs, a set of three panels

used as an altarpiece, are still in the Venice Accademia, and

two "Pietās," both in Milan, are all from this early period. His

early work is well exemplified in two beautiful paintings now

in the National Gallery of London, "The Blood of the

Redeemer" and "The Agony in the Garden."

In all his early pictures he worked with tempera, combining

the severity and rigidity of the Paduan school with a depth of

religious feeling and human pathos all his own. His early

Madonnas, following in his father's tradition, are mostly

sweet in expression, but he substituted for a mainly decorative

richness one drawn more from a sensuous observation of

nature. Although the pronounced linear element--i.e., the

dominance of line rather than mass as a means of defining

form, derived from the Florentine tradition and from the

precocious Mantegna--is evident in the paintings, the line is

less self-conscious than Mantegna's work, and, from the first,

broadly sculptured planes offer their surfaces to the light from

a dramatically brilliant sky. From the beginning Giovanni

Bellini was a painter of natural light, as were Masaccio, the

founder of Renaissance painting, and Piero della Francesca, its

greatest practitioner at that time. In these earliest pictures the

sky is apt to be reflected behind the figures in streaks of water

making horizontal lines in a mere strip of landscape. In "The

Agony in the Garden," the horizon moves up, and a deep, wide

landscape encloses the figures, to play an equal part in

expressing the drama of the scene. As with the dramatis

personae, the elaborately linear structure of the landscape

provides much of the expression, but an even greater part is

played by the colours of the dawn, in their full brilliance and

in the reflected light within the shadow. This is the first of a

great series of Venetian landscape scenes that was to develop

continuously for a century or more. To a city surrounded by

water, the emotional value of landscape was now fully

revealed.

The great composite altarpiece with St. Vincent Ferrer, which

is still in the church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, was

painted perhaps 10 years later, toward the mid-1470s. But the

principles of composition and the method of painting had not

yet changed essentially; they had merely grown stronger in

expression. It seems to have been during a voyage down the

Adriatic coast, made probably not long afterward, that Bellini

encountered the influence that must have helped him most

toward his full development: that of Piero della Francesca.

Bellini's great "Coronation of the Virgin" at Pesaro, the first

Venetian picture in the full style of the Renaissance, probably

reflects and carries still further in composition the ideas

expressed by Piero in an unrecorded "Coronation of the

Virgin," the lost centrepiece of a polyptych originally in the

church of S. Agostino at Borgo Sansepolcro. Christ's

crowning of his Mother beneath the effulgence of the Holy

Ghost is a solemn act of consecration, and the four saints who

stand witness beside the throne are characterized by their deep

humanity. Every quality of their forms is fully realized: every

aspect of their bodies, the textures of their garments, and the

objects that they hold. As with work by Masaccio and Piero

della Francesca, the perspective and the polychrome of

pavement and throne help to establish the group in space, and

the space is enlarged by the great hills behind and rendered

infinite by the luminosity of the sky, which envelops the scene

and gathers all the forms together into one. Harmony is the

aim of all art, but the significance of the harmony depends

upon the significance of its parts, as well as upon the degree of

its intensity. Here, Bellini has provided humanity with the full

grandeur of nature, and it is nature endowed with all that is

religious in man. The unity achieved has an emotional warmth

that is uniquely his.

A new degree of technical achievement is implied. The fact

that at this point Giovanni painted mainly in oil does not

completely explain his greatness. Piero was one of many

Italian painters who were already using the oil medium. A

legend that Giovanni ceased to paint in tempera only after he

was introduced to oils by Antonello da Messina, who was in

Venice in 1475/76, is without point, for much the same effects

can be produced in either medium.

It is the way of using the medium that makes the

difference--and that depends upon the painter's intentions and

upon his vision. It was Bellini's richer and wider vision that

determined his future development. Oil paint is inclined to be

the more transparent and fusible and therefore lends itself to

richer colour and tone by allowing a further degree of glazing,

the laying of one translucent layer of colour over another. It is

this technique and the unprecedented variety with which he

handled the oil paint that gives his fully mature painting the

richness associated with the Venetian school.

Giovanni's brother Gentile was chosen by the government to

continue the painting of great historical scenes in the hall of

the Great Council in Venice; but in 1479, when Gentile was

sent on a mission to Constantinople, Giovanni took his place.

From that time to 1480 much of Giovanni's time and energy

was devoted to fulfilling his duties as conservator of the

paintings in the hall, as well as painting six or seven new

canvases himself. These were his greatest works, but they were

destroyed when the huge hall was gutted by fire in 1577. We

can now only gain an approximate idea of their design from

"The Martyrdom of St. Mark" in the Scuola di S. Marco in

Venice, finished and signed by one of Giovanni's assistants,

and of their execution from Giovanni's completion of

Gentile's "St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria" after his

brother's death in Venice in 1507.

Yet a surprisingly large number of big altarpieces and

comparatively portable works have survived and show the

steady but adventurous evolution of his work. The principles

and the technique of the Pesaro altarpiece find their full

development in the still larger Madonna altarpiece from S.

Giobbe in the Venice Accademia, where the Virgin enthroned

in a great apse and the saints beside her seem ready to melt

into the reflected light. This seems to have been painted before

the earliest of his dated pictures, the half-length "Madonna

degli Alberetti," also in the Venice Accademia, of 1487.

While for the first 20 years of Giovanni's career the subject

matter was limited mainly to Madonnas, Pietās, and

Crucifixions, toward the end of the century it began to be

greatly enriched not so much by the wider choice of subjects,

which were still mainly religious, as by the development of

the mise-en-scčne, the physical setting of the picture. He

became one of the greatest of landscape painters. His study of

outdoor light was such that one can deduce not only the season

depicted but almost the hour of the day.

Bellini also excelled as a painter of ideal scenes; i.e., scenes of

primeval as opposed to individualized images. For the "St.

Francis in Ecstasy" of the Frick Collection or the "St. Jerome

at His Meditations," painted for the high altar of Sta. Maria

dei Miracoli in Venice, the anatomy of the earth is studied as

carefully as those of human figures; but the purpose of this

naturalism is to convey idealism through the realistic portrayal

of detail. In the landscape "Sacred Allegory," now in the

Uffizi, he created the first of the dreamy enigmatic scenes for

which Giorgione, his pupil, was to become famous. The same

quality of idealism is to be found in his portraiture. His "Doge

Leonardo Loredan" in the National Gallery, London, has all

the wise and kindly firmness of the perfect head of state, and

his "Pietro Bembo" (?) in the British royal collection portrays

all the sensitivity of a poet.

Both artistically and personally the career of Giovanni Bellini

seems to have been serene and prosperous. He lived to see his

own school of painting achieve dominance and acclaim. He

saw his influence propagated by a host of pupils, two of whom

surpassed their master in world fame: Giorgione, whom he

outlived by six years, and Titian.

The only personal description extant of Giovanni is from the

hand of Albrecht Dürer, who wrote to the German humanist

Willibald Pirkheimer from Venice in 1506 ". . . everyone tells

me what an upright man he is, so that I am really fond of him.

He is very old, and still he is the best painter of them all."