|

|

Summer 2016, Web Issue 18

A multidisciplinary

journal in the

arts and politics

Paintings & Prints

Poetry & Prose

Virtual Facsimiles

Founding Editors:

Joe Brennan

Carlo Parcelli

Contributing Editors:

Bradford Haas

Rosalie Gancie

Cathy Muse

Mark Scroggins

Jim Angelo

Web Editors:

JR Foley

Rosalie Gancie

Nicole Foley

-

[ David Jones's ] work reveals a complex and acute cultural awareness, both of the challenges of Imperialism and “technocracy” in the mid-twentieth century and of his own personal roots in artistic and literary modernism, Celtic culture and Catholic Christianity. What we meet in reading a text or viewing a work by David Jones is an artist in the process of making, and aware of the dynamic character of a work of art.We are not so much deciphering or admiring a finished product as we are discovering traces of the activity of making, in this artist’s particular experience, an activity that he associates with a sacred dimension of human life.

- Kathleen Henderson Staudt

from her Introduction

All essays, poetry, fiction, and artwork are copyrighted in the

names of the authors and artists,

to whom all rights revert.

David Jones Conference

March 29 & 30, 2012

Carlo Parcelli:

Book / Author page

Magus Magnus

Book / Author page

Wayne Pounds

Book / Author page

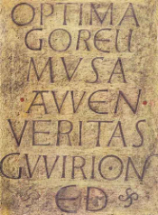

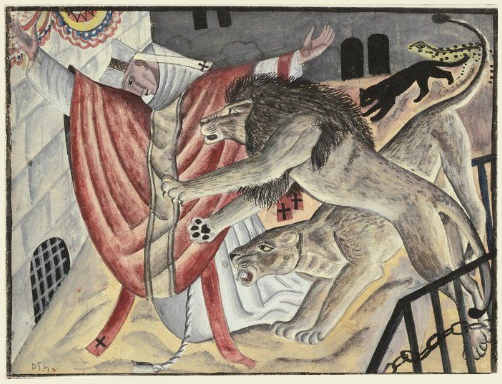

@ Courtesy Estate of David Jones

David Jones, Martyrdom, 1927

watercolour, pencil and black ink

__________________

|

David Jones Culture & Artifice

A Collection of Essays

Introduction by

|

Gregory Baker

‘An edition of Jones's address to the University

of Wales on receiving the honorary degree of

Litterarum Doctor, 15 July 1960’

Jasmine Hunter-Evans

‘Bridging the Breaks:

David Jones and the Continuity of Culture’

Thomas Goldpaugh

‘The Signum of Some Otherness:

David Jones and a Eucharistic Theory of Art’

Kathleen Henderson Staudt

“Acts of Ars” in David Jones's

The Anathemata & W.H. Auden's Horae Canonicae

Thomas Dilworth

‘David Jones and the Celtic Tradition

in English Literature’

Malcolm Guite

‘Incarnation, Bodies and Locality:

The Incarnational Thrust of David Jones's Art’

Paul Robichaud

‘Images of Making in the Poetry of David Jones’

William F. Blissett

‘David Jones: Seventy Years with David Jones’

Fr. Dominic White, O.P & Sr. Rose Rolling, O.P.

‘Minor Prophets: David Jones and Contemporary Art at Blackfriars, Cambridge’

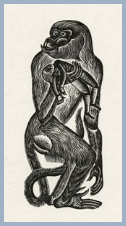

from Bradford Haas:

| Culture & Artifice:

The Major Book Illustrations of David Jones |

|

|

Jon Woodson

two selections from his new book Summer Games: A Novel ‘Diabasis’ plus |

| ‘Bonus

Army’ |

|

|

Luciana Bohne Pasolini's St. Paul: a Prophecy of Our Times? a review his notes on his unmade film

|

|

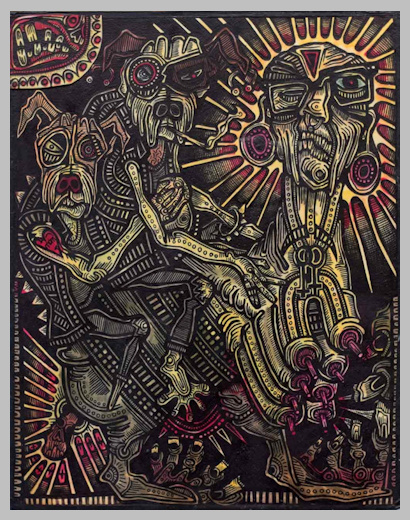

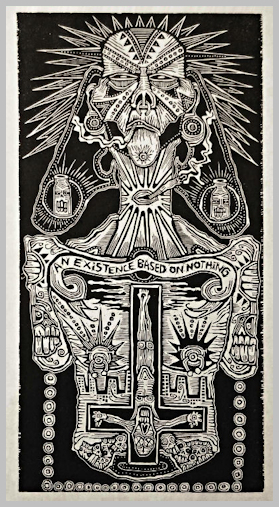

Tim Wengertsman

Woodcuts

plus: |

|

Joan McCracken The Swallow and Ode to a Nightingale |

|

Peter Dale Scott

from his

Walking on Darkness |

| |

|

Carlo Parcelli (after Peter Dale Scott) |

|

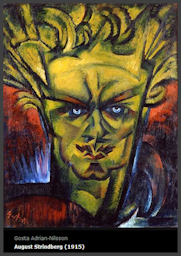

John Ryskamp

‘Strindberg on Meth’

|

|

| |

|

JR Foley Robert Coover's Huck Out West a review |

| |

|

JR Foley Robert Coover's Going for a Beer a review |

| |

|

Carlo Parcelli Part II [Dog Bite in Exile]

Monologue for |

|

Pete O'Brien

|

|||

|

whistles the jackdaw

[11 haiku] 29 may 2016: 29 may 2016: four poems |

||

|

|

|||

|

plus

A Sheaf of Flashes 4 |

|||

|

|||

In this issue...

DAVID JONES returns!

FlashPøint #13,

Spring 2010, showcased

the art of Welsh poet and painter David Jones, as well as scholarly reflections on his

poetry. Two years later the David Jones Society held a new conference on Jones at

Washington Adventist University in Takoma Park, Maryland. This issue of

FlashPøint features papers presented at that

conference.

Kathleen Henderson Staudt introduces a host of essays by Thomas Dilworth on

Jones and the Celtic tradition in English literature, Jasmine Hunter-Evans on

“breaks” and “bridges” in the continuity of culture, Thomas Goldpaugh

and Staudt herself on

different significant aspects of Jones's The Anathemata, Malcolm Guite on the

“Incarnational thrust” of Jones's art, Paul Robichaud on the key

Jonesian theory of “making,” Gregory Baker's edition

of an address by Jones to the University of Wales in 1960, as well as William F. Blissett's

reflections on new directions for projects on Jones's work in light of his own

friendship with the poet/painter.

Fr. Dominic White, O.P. and Sr. Rose Rolling, O.P.

introduce a 2021 exhibition of art/word as ‘creative deed’ in David Jones and Contemporary Art at Blackfriars, Cambridge.

FlashPøint editor

Bradford Haas adds a rich sheaf of Culture & Artifice: The Major Book Illustrations of David Jones following Jones's

explorations of word and image in the prose tales of others, including The Book of Jonah, The Chester Play of the Deluge, and The Rime of the

Ancient Mariner.

David Jones has further

company in this issue of FlashPøint. One wonders what painter Jones

would think of Tim

Wengertsman's work, but at the very least it would likely leave him arrested, not

to say mesmerized.

John Ryskamp's new play, “The Curtain Rises on the Revolution”, has startled one reader to write:

Heady company for Master

Jones!

Even headier, Robert Coover takes (off) on a boyhood contemporary of Jones—Mark Twain—as he imagines what Twain did not—Huck Finn's (and Tom Sawyer's) later adventures after &ldquot;lightin' out for the Territory.” JR Foley booknotes Coover's new Huck Out West…as well as a brand-new selection of Coover's short fictions, circa 1962ř2016, entitled Going for a Beer. These shorties are never less than either funny or scary…or both at once.

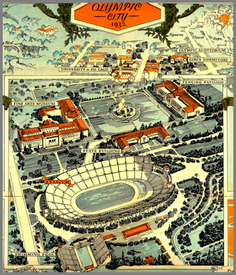

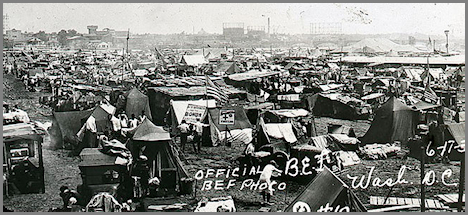

More heady company comes in

the form of two episodes, “Bonus Army” and “Diabasis,” from Jon

Woodson's new novel, “Summer Games,” wherein four Black grad students drive

cross-country from Washington, D.C., and the Bonus Army camp on Anacostia Flats,

to the 1932 Olympic Summer Games in Los Angeles. Let it not be said that the tales

of Woodson are ever exercises in historical naturalism.

Nor, for that matter, are the fictions of Pete O'Brien, who returns to FlashPøint with a “Sheaf of Flashes 4,” plus “whistles the jackdaw” and “29 may 2016: four poems.”

Pete O'Brien also presents FlashPøint readers with a Clarice Lispector Special!

celebrating the Brazilian novelist who contributed her own gender-bending, image-smashing storytelling innovations to the Nueva Novela Hispanoamericana.

The six-page Special! explores Clarice's life and works as well as her impact on others, especially storytellers and poets writing today.

In "The Swallow" Joan McCracken

takes us further into the passion and exuberant vision of Miriam amid lovers past and

future. Then one of the lovers remembers Miriam in Ode to a Nightingale.

But this seems game-playing in

the face of what Pier Paolo Pasolini attempted in his never&$45;produced screenplay

St. Paul, which retold the early days of Christianity—transplanted to

Nazi-dominated France—before, as Pasolini shows it, Satan and St. Luke turned it

into a Church. Luciana Bohne in recounting the scenario asks: is it “a

prophecy of our times?”

And Ictus bites again! Canus Ictus, fool and gadfly exiled by Rome, wanders his isle of bones

and skulls reminiscing of orgies and massacres past, invoking ghostly Spartacus,

shipwrecks, battles with Spartoi, and the last time he and Loquatia wasted no time.

With Peter Dale Scott's Walking on Darkness set to appear later this year, FlashPøint is proud to present

Six Poems from this new collection.

Inspired by Peter Dale Scott's poem

Tavern Underworld, Carlo Parcelli gives us More Fun House East, 1969 weaving two personal, polar opposite experiences into a helix of insight.

Enjoy FlashPøint #18!

A Comment on this issue...

Some might wonder why we're juxtaposing works by the avowedly religious David

Jones with a piece about the Marxist filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini's unfinished film

‘St. Paul,’, the art work of the Punk woodcut artist Tim Wengertsman, and the work of

the avowedly irreligious poet Carlo Parcelli.

But the juxtapositions are connected by a moral & aesthetic thread. David Jones shied

away from the blasphemous curses of his Cockney WWI trench comrades, but he

described their inherent power as ‘almost liturgical,’ And Pasolini noted that “Every

blasphemy is a sacred word.”

Jones felt technology & modernity impoverished contemporary society. In his 1959

statement to the Bollingen Foundation he remarked that:

There's a strong desire for social justice in our four artists—a desire for a way to

expose the brutality imposed by humankind on one another.

As one critic put it, Pasolini often used “religious/mythic imagery to ground a political

critique.”

In the David Jones painting “Martyrdom” above, St. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, is attacked by

lions as punishment for his refusal to renounce his faith. He's frightened, and his

vestments prove an insubstantial armor against the lions' attack. Eric Gill said of Jones

that:

Carlo Parcelli uses the Roman Imperium in his poetic monologues as metaphor for our

current Western Imperialist age. But his characters don't look to the spiritual. Instead

they predict a hunger for recourse with the same ferocity that matches that of the lion.

As one of his characters says, “The meek will stand a bear up in a pen if it's

meat.”

—Pasolini: The Sacred Flesh

All David Jones images are reproduced by the kind permission of the David Jones Estate. We are eager to hear

from you, especially about this issue, so please tell

us what you think: flashpnt@hotmail.com!

Catchwords & banalities storm through & about the

protagonist in John Ryskamp's “The Curtain Rises on the Revolution,” pummeling

outward into single-sentence vignettes. Does he swat them off or is he batting them

forward? From the play:

“Ryskamp likes to guide his audience two fingers in the nostrils back to the stage.”

and “Are we dreaming Ryskamp or is he dreaming us?”

“For now the artist becomes, willy-nilly, a sort of Boethius, who has been nicknamed

‘the Bridge,’ because he carried forward into an altogether metamorphosed world

certain of the fading oracles which had sustained antiquity.”

This comports with Pasolini's views. For Pasolini, as critic Stefania Benini has noted,

“The sacred embodies the nemesis of modernity.” Benini summarizes Pasolini's views

from his notable 1970 interview with Jean Duflot:

“He looks back nostagically to the mythical relationship of ancient civilizations with

nature and the earth from the extreme margins of the ‘universo orrendo’ (‘horrendous

universe’) perceived, from a Marxist perspective, as the dominion of bourgeois

homogenization and consumerism.”

And Jones continues with what could apply to Tim Wengertsman's desire to document

the otherwise marginilazed Punk subculture of himself and his friends in Hartford, CT:

“My view is that all artists […] are in fact ‘showers forth’ of things which tend to be

impoverished, or misconceived, or altogether lost or wilfully set aside in the

preoccupations of our present intense technological phase, but which, none the less,

belong to man.”

In Wengertsman's work we see a powerful yearning for comraderie and meaning. The

meaning often comes through the physical/spiritual use and misuse of drugs &

alcohol, but the desire for what's holy to him & his companions is annointed in his

work by the use of halos & other religious iconography. Wengertsman is satirical but

calls justifiably for empathy, asking us to feel the pathos of the lives of his subjects

along with the humor.

‘We should miss the quality of his work if we did not see that it is a combination of

two enthusiasms, that of the man who is enamoured of the spiritual world and at the

same time as much enamoured of the material body in which he must clothe his

vision.’

The lions depict the instinctive, brutal force of nature but also the ferocious desire for

power on the part of the men who placed the Saint there, men such as those who gave

us World War I.

Sources:

Stefania Benini, U.of Toronto Press (2015)

—Saint Paul: A Screenplay, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alain Badiou

Ward Blanton,

Elizabeth Castelli (Translator). Verso (2014)

—Martyrdom, 1927, David Jones, watercolour, pencil & black ink

via www.waterman.co.uk

/ with Eric Gill quote:

Paul Hills, ‘The Art of David Jones’ from David Jones, Tate

Gallery, London, exhibition catalogue, 1981, p19.